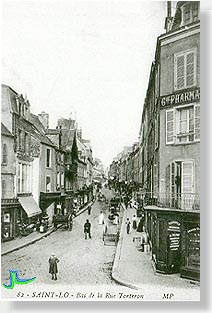

Saint-Lô was a sleepy little town before the war, and even more so during the German occupation. After the arrival of the German army in June 1940, life went on, in a more or less normal way, for nearly four long years. People went to work, children went to school, there were movies, plays and country fairs, all tightly controlled and regimented by the occupants. In spite of the restrictions, the inhabitants suffered less than people in larger cities did. Because it was an important market center, there were numerous contacts between rural and urban folks, and the countryside, so close, provided potatoes, butter, eggs, milk and poultry in reasonable quantities. However, under a veneer of quiet submission, more ominous currents developed quickly. The resistance was very active, especially at the post office and the railway station:  Telephone equipment was stolen and hidden in remote farms, official German mail did not get delivered, often saving young men from forced labor in Germany. Railroad tracks were sabotaged. After radios had been confiscated, a network of BBC listening posts was installed throughout the town, including in the post office. A telephone line that the Germans had requested to link Saint-Lô with the Island of Jersey, never functioned.

Telephone equipment was stolen and hidden in remote farms, official German mail did not get delivered, often saving young men from forced labor in Germany. Railroad tracks were sabotaged. After radios had been confiscated, a network of BBC listening posts was installed throughout the town, including in the post office. A telephone line that the Germans had requested to link Saint-Lô with the Island of Jersey, never functioned.

But in the spring of 1944, new dangers loomed. On Sunday, June 4th, Mme Dubois wrote to her daughter-in-law: "The area around Saint-Lô is bombed every day, especially the railroad junction on the Paris-Cherbourg line. The other night, 32 houses were destroyed. Luckily everybody had escaped in the fields and there were no victims. Here, our house shook a lot. Last night, same thing again. We could not sleep. Bombs were falling all around us. Every day, hundreds of planes fly over us, and there are 7 or 8 alerts. Buses and trains are strafed regularly, and there have been several victims. We don't understand what is going on. We have no gas, no electricity, and water for only a few hours a day. I hope it will be over soon".

On Monday, June 5, a kind of malaise settled on the town: more planes than usual were flying overhead, German troops came and went nervously, sheltering their trucks under the trees. And then, rumors started to fly faster and louder than a Mustang crossing the sky. Mme Turboult was finishing her last music class: "I heard a knock on the door: a student came in, bringing a note for my colleague upstairs: "The Allies are landing tonight!" I left my room to show it to the school director, we did not really want to believe it, and I came back to finish my class as usual."

On Monday, June 5, a kind of malaise settled on the town: more planes than usual were flying overhead, German troops came and went nervously, sheltering their trucks under the trees. And then, rumors started to fly faster and louder than a Mustang crossing the sky. Mme Turboult was finishing her last music class: "I heard a knock on the door: a student came in, bringing a note for my colleague upstairs: "The Allies are landing tonight!" I left my room to show it to the school director, we did not really want to believe it, and I came back to finish my class as usual."

At 9:15 p.m., those who had a radio were listening to the BBC. Slowly, one after the other, repeated twice, the messages fell, and members of the resistance understood: "The Cotentin is a peninsula": The landings would be in Normandy. "The dice are thrown", was the order for the resistance to cut telephone lines, and most important: "The sirens will have bleached hair": It is true then, the Allies would be landing tonight!

At 9:15 p.m., those who had a radio were listening to the BBC. Slowly, one after the other, repeated twice, the messages fell, and members of the resistance understood: "The Cotentin is a peninsula": The landings would be in Normandy. "The dice are thrown", was the order for the resistance to cut telephone lines, and most important: "The sirens will have bleached hair": It is true then, the Allies would be landing tonight!

The night of June 5 was going to be different from all the ones before. Many would sleep as usual, but some, in spite of the curfew, would roam the streets, in excitement and fear. German soldiers were hurrying about, looking for their officers. The anti-aircraft batteries fired continuously, illuminating the sky with tracers. Mme Dubois, too anxious to sleep, started writing a letter to her family:  "Since 10 last night, guns are thundering by the coast without respite. They must be big naval guns, they are so loud, and not too far away. Bombs are exploding all over, planes fly by at high speed, the flak keeps firing. It is very scary. Are we going to get hit? Is this the Allied landing? There is a lot of movement in the streets. A fire truck passes by. There is a fire, but where? What an awful night. It seems that the guns are getting closer. Everyone is up. What is going on? Is this the beginning of the end? It seems that the house is going to crumble, doors and windows are shaking so hard."

"Since 10 last night, guns are thundering by the coast without respite. They must be big naval guns, they are so loud, and not too far away. Bombs are exploding all over, planes fly by at high speed, the flak keeps firing. It is very scary. Are we going to get hit? Is this the Allied landing? There is a lot of movement in the streets. A fire truck passes by. There is a fire, but where? What an awful night. It seems that the guns are getting closer. Everyone is up. What is going on? Is this the beginning of the end? It seems that the house is going to crumble, doors and windows are shaking so hard."

By 7 a.m. on June 6, everybody was already up and out in the street. The same words were on everyone's lips: "The Allies have landed!" Mr. De Saint-Jorre wrote in his journal: "On faces drawn by emotion and lack of sleep, a certain joy is evident. When German trucks pass by, smiles full of irony seem to say "They are leaving, at last". We all believed then that the Germans would leave without a fight, that the Americans would be here to-morrow, to-night maybe".

"It felt like a Sunday. We laughed, we talked, we were excited. It was like the last class before graduation. Nobody is working, we want to forget everything. Good bye monotony, good riddance routine! It is the beginning of the extraordinary. I see people who a few days ago ignored each other, warmly shake hands."

"It felt like a Sunday. We laughed, we talked, we were excited. It was like the last class before graduation. Nobody is working, we want to forget everything. Good bye monotony, good riddance routine! It is the beginning of the extraordinary. I see people who a few days ago ignored each other, warmly shake hands."

By 9 a.m. two posters appeared on the walls, yellow, framed in black: the official mean of communication of the occupation forces, which, for four years, meant more restrictions and interdictions. They forbade all gathering in the streets, and demanded that people stay at home, behind closed - but unlocked - doors.

Employees were sent home as soon as they arrived at the office. Exams at the teachers' college were canceled. The principal of the boarding school for girls did everything she could to send home her pupils who lived in the country, by horse cart, bicycle or on foot. Mr. Menat, head of the Passive Defense Group, the local rescue unit, headed for the office of the Kreisskommandantur to get the special badges his men needed to perform their duties: "I am received right away by Von Bulow, who asks me: " Why do you want your badges now? Why is it so urgent? Tell me, you can trust me, we are alone." I simply answer that he must know what is going on since midnight. Von Bulow then asks me to follow him, we go down to the courtyard. A few trucks are parked in a circle, they are full of Allied paratroopers, their faces black and tired. And so I had to pass these captured soldiers in review, like a collaborator."

Around midday, the main electric transformer was bombed by two American planes, which destroyed it with just two bombs. The town lost power, and its radios. Some people saw a good sign in this: the Allies were pinpointing their targets, and the population did not have to worry. For others, it was a bad omen, precursor of worst assaults to come.

The afternoon started in relative tranquillity, with only the far away rumblings of guns echoing through the clouds.  Then, at around 4:30 p.m., a group of about 15 planes appeared over the town, flying very low, in all directions. They assembled and spun around the train station like moths around a light. The first one left the group, dove toward the station, dropped its bomb and climbed up above the others. Each of the planes, one after the other, ignoring the German anti-aircraft guns, went through the same routine." We could only hear the raw metallic scream of the engines, accelerating, slowing down, diving, climbing, the clacking of the machine guns and the dull explosions of the bombs." This was enough for some people, who had relatives in the country, to leave their homes and seek refuge away from the city.

Then, at around 4:30 p.m., a group of about 15 planes appeared over the town, flying very low, in all directions. They assembled and spun around the train station like moths around a light. The first one left the group, dove toward the station, dropped its bomb and climbed up above the others. Each of the planes, one after the other, ignoring the German anti-aircraft guns, went through the same routine." We could only hear the raw metallic scream of the engines, accelerating, slowing down, diving, climbing, the clacking of the machine guns and the dull explosions of the bombs." This was enough for some people, who had relatives in the country, to leave their homes and seek refuge away from the city.

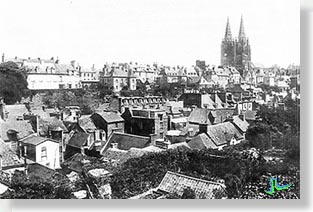

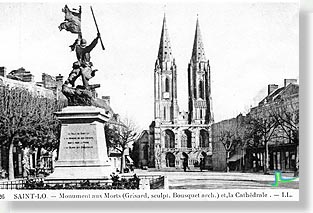

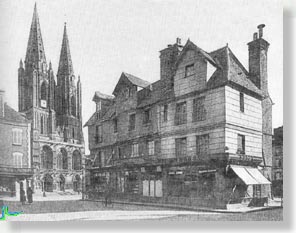

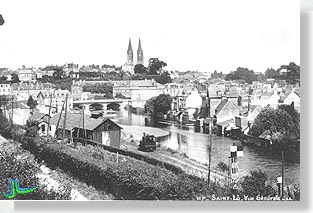

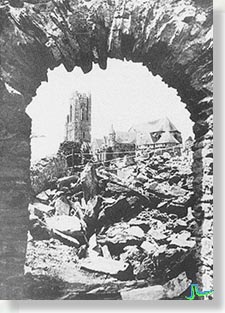

"Dusk is falling. All is calm and serene. After dinner, from the patio of the school, we were gazing at the town on its rocky spur, below a vast circle of green pastures. The last rays of the sun fell on the twin spires of the cathedral. A distant drone slowly grew into a loud whirring sound. We looked up. Our practiced eyes uncovered a plane formation. Slowly, they got larger, their huge wings diaphanous against the darkening sky. They barely seem to move, staying in an impeccable order, a majestic image of fatality. A cry of joy salutes them: The flying fortresses. And one wonders..." So Mr. Herpin recalled the coming of the bombers. Mr. Chevillon was fetching water at a public fountain when he saw two small planes leave the group, each trailing behind them a narrow plume of white smoke, marking the tragic corridor for the first bombardment of Saint-Lô. He ran into a public toilet for shelter.

"Dusk is falling. All is calm and serene. After dinner, from the patio of the school, we were gazing at the town on its rocky spur, below a vast circle of green pastures. The last rays of the sun fell on the twin spires of the cathedral. A distant drone slowly grew into a loud whirring sound. We looked up. Our practiced eyes uncovered a plane formation. Slowly, they got larger, their huge wings diaphanous against the darkening sky. They barely seem to move, staying in an impeccable order, a majestic image of fatality. A cry of joy salutes them: The flying fortresses. And one wonders..." So Mr. Herpin recalled the coming of the bombers. Mr. Chevillon was fetching water at a public fountain when he saw two small planes leave the group, each trailing behind them a narrow plume of white smoke, marking the tragic corridor for the first bombardment of Saint-Lô. He ran into a public toilet for shelter.

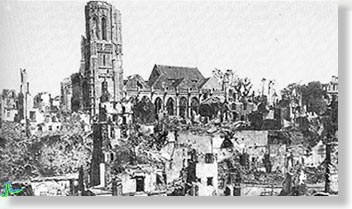

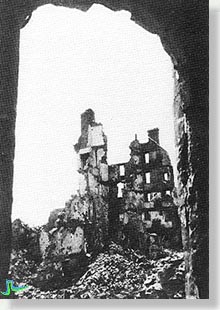

The bombs fell, tiny black specks at first, on a slanted path, with a frightening hissing sound. Mr. Bernard would describe it later as "noise of a thousand water hoses sweeping a street, noise of a mighty torrential stream, increasing second by second; terrifying noise, heart-throbbing, high-pitched, sliding into a murderous shriek before the cataclysmic explosion that finally smothers it. Three times, death came screaming over the town on June 6 at eight in the evening. Three times only, for each squadron of Marauders, at two seconds intervals, dropped its entire load at once - forty bombs, 20,000 pounds of explosives and steel. In just six seconds, 60,000 pounds of bombs had cut a deadly swath from one end of the town to the other, a smoldering chasm."

The bombs fell, tiny black specks at first, on a slanted path, with a frightening hissing sound. Mr. Bernard would describe it later as "noise of a thousand water hoses sweeping a street, noise of a mighty torrential stream, increasing second by second; terrifying noise, heart-throbbing, high-pitched, sliding into a murderous shriek before the cataclysmic explosion that finally smothers it. Three times, death came screaming over the town on June 6 at eight in the evening. Three times only, for each squadron of Marauders, at two seconds intervals, dropped its entire load at once - forty bombs, 20,000 pounds of explosives and steel. In just six seconds, 60,000 pounds of bombs had cut a deadly swath from one end of the town to the other, a smoldering chasm."

To leave or to stay? The residents were faced with a tragic dilemma. Mr. Delaunay believed that the bombing was a mistake and that it would not happen again. He planned to spend the night in his house, but his daughter was so terrified that the family finally went to a shelter. The majority, however, walked away from the ruins, escaping through narrow country lanes sunken between dense hedgerows that provided cover and a sense of security. Mr. Herpin, a teacher at the boarding school, left with his family and some of his students: "When we arrived at the farm, the courtyard was already full of people. The farmer and his family were doing their best to find shelter for everyone. We are led to an attic with a thick layer of straw on the floor. Night falls slowly. It is very quiet, as if nothing had happened. Two large German planes fly by at treetop level, as if hiding. They are losers already, we will never see the likes of them again. For many, it is their first night on straw. It is dry, but hard, the farmer did not have time to loosen up the bales, and it is infested with small insects that sting and tickle. Soon, in the badly ventilated attic, the air becomes heavy with dust."

To leave or to stay? The residents were faced with a tragic dilemma. Mr. Delaunay believed that the bombing was a mistake and that it would not happen again. He planned to spend the night in his house, but his daughter was so terrified that the family finally went to a shelter. The majority, however, walked away from the ruins, escaping through narrow country lanes sunken between dense hedgerows that provided cover and a sense of security. Mr. Herpin, a teacher at the boarding school, left with his family and some of his students: "When we arrived at the farm, the courtyard was already full of people. The farmer and his family were doing their best to find shelter for everyone. We are led to an attic with a thick layer of straw on the floor. Night falls slowly. It is very quiet, as if nothing had happened. Two large German planes fly by at treetop level, as if hiding. They are losers already, we will never see the likes of them again. For many, it is their first night on straw. It is dry, but hard, the farmer did not have time to loosen up the bales, and it is infested with small insects that sting and tickle. Soon, in the badly ventilated attic, the air becomes heavy with dust."

While most of the residents fled in the country or hid in shelters, some were canvassing the ruins, looking for survivors or tending to the wounded. Mr. Leclerc was called by a young boy, whose brother and sister were buried under their house.  "We dig through stones, bricks, earth, clothes, things. We throw mementos at the feet of the mother, who collects them in a neat little pile. It goes on for hours, and night falls. Some men leave, to go across the street, there are six victims under the ruins, a whole family. We find the remains of a bed, the boy's bed, empty. We keep looking,.... What for? There can only be squashed bodies in there, under such a mass of burnt beams, collapsed walls and plaster dust. Then, suddenly, a hand touches something soft. It is tiny, and warm. We dig deeper, faster, half an hour more, and now, a muted yell. We find the foot, the leg, blood. At last, we retrieve the little mass of living flesh, covered with dust. Now, the only light comes from the fires. The little boy is still in there. We go back to work. A new miracle, a cry :"Mommy". He wants to cry, he does not understand. "What happened?" A priest, his black habit covered with white dust passes by on his way to the hospital, we give him the little girl, he takes her in his arms. She is dead."

"We dig through stones, bricks, earth, clothes, things. We throw mementos at the feet of the mother, who collects them in a neat little pile. It goes on for hours, and night falls. Some men leave, to go across the street, there are six victims under the ruins, a whole family. We find the remains of a bed, the boy's bed, empty. We keep looking,.... What for? There can only be squashed bodies in there, under such a mass of burnt beams, collapsed walls and plaster dust. Then, suddenly, a hand touches something soft. It is tiny, and warm. We dig deeper, faster, half an hour more, and now, a muted yell. We find the foot, the leg, blood. At last, we retrieve the little mass of living flesh, covered with dust. Now, the only light comes from the fires. The little boy is still in there. We go back to work. A new miracle, a cry :"Mommy". He wants to cry, he does not understand. "What happened?" A priest, his black habit covered with white dust passes by on his way to the hospital, we give him the little girl, he takes her in his arms. She is dead."

Shortly after midnight, again the planes came. Mr. Bernard opened his windows: I "sat in my office, looking over the town. The first plane suddenly spat out a tracer rocket. Straight as an arrow, it was aimed at the city center. A ball of fire sprang out where it fell."

Mr. Lefrancois, looking from a small opening in the wall of a shelter, remembers "an intense light, cherry red". Mr. Bernard continues: "With a deafening noise, bombs keep falling, and I cannot distinguish individual explosions. It becomes a continuous hellish rumbling, laced with the frightening screech of engines and the deadly whistling of falling bombs. From the sea of fire boiling in front of me, erupt blinding lighting strikes and geysers of sparks. In minutes, the whole west side of the town was an immense inferno, its reddish yellow glow reverberating in the sky between huge columns of smoke. From time to time, their underbelly catching the light of a thousand fires, three or four planes would wind around the swirling columns of smoke, like fish in an aquarium full of aquatic plants - Horsemen of the Apocalypse, riding across the red sky, to the sound of an infernal orchestra, made up of colossal gongs, titanic cymbals and gigantic drums, sowing in their wake terror, misery, destruction and death."

Mr. Lefrancois, in his shelter, felt "that the town is like caught in a net, and that we are waiting the "coup de grace"...Second after second, we wait. The first strings of bombs sounds like a train arriving at a station at high speed, the ground shakes...And then came the avalanche. We seem so close to the impact, the explosions blind us, they throw us against one another, against the walls. Are we still alive, are we still sane? I don't see the lightning of the explosions anymore, it is difficult to breathe, our mouths fill with concrete and plaster dust. And then, it stops, the roar of the planes goes on diminishing. Nobody speaks. It is dark.

Mr. Lefrancois, looking from a small opening in the wall of a shelter, remembers "an intense light, cherry red". Mr. Bernard continues: "With a deafening noise, bombs keep falling, and I cannot distinguish individual explosions. It becomes a continuous hellish rumbling, laced with the frightening screech of engines and the deadly whistling of falling bombs. From the sea of fire boiling in front of me, erupt blinding lighting strikes and geysers of sparks. In minutes, the whole west side of the town was an immense inferno, its reddish yellow glow reverberating in the sky between huge columns of smoke. From time to time, their underbelly catching the light of a thousand fires, three or four planes would wind around the swirling columns of smoke, like fish in an aquarium full of aquatic plants - Horsemen of the Apocalypse, riding across the red sky, to the sound of an infernal orchestra, made up of colossal gongs, titanic cymbals and gigantic drums, sowing in their wake terror, misery, destruction and death."

Mr. Lefrancois, in his shelter, felt "that the town is like caught in a net, and that we are waiting the "coup de grace"...Second after second, we wait. The first strings of bombs sounds like a train arriving at a station at high speed, the ground shakes...And then came the avalanche. We seem so close to the impact, the explosions blind us, they throw us against one another, against the walls. Are we still alive, are we still sane? I don't see the lightning of the explosions anymore, it is difficult to breathe, our mouths fill with concrete and plaster dust. And then, it stops, the roar of the planes goes on diminishing. Nobody speaks. It is dark.  We realize that the opening has been filled. We have no shovel, no pick, and we have to dig out with our bare hands. As soon as we get out, we hear a plane again, a single plane, and we rush back inside. But it is just a photographer plane. What lugubrious images is it going to bring back to the lab in England? Again we leave the shelter. The house is gone, the street is gone."

We realize that the opening has been filled. We have no shovel, no pick, and we have to dig out with our bare hands. As soon as we get out, we hear a plane again, a single plane, and we rush back inside. But it is just a photographer plane. What lugubrious images is it going to bring back to the lab in England? Again we leave the shelter. The house is gone, the street is gone."

From the shelter of his barn, Mr. Herpin saw the "bombed out" arrive at the farm, "absolute ghosts barely able to stand on their broken limbs; their faces pale and scarred, their eyes staring into space, their hair plastered with dust. Their clothes, when they have any left, are torn, they are covered with bloody wounds. And above all, I remember that awful impression of seeing fellow human beings, acquaintances, friends, so deprived of everything, so humiliated, so broken, from whom all dignity had been stolen, brought down to the level of exhausted beasts...And yet we are seeing only the lucky ones, those who, against all hope, were able to escape being crushed or burnt to death. There are nearly no complete families: here, it is a mother with her child, there a grandmother and her grandson, or a father alone. Some speak with their eyes down, and, listening to them, one can guess at the tragedy of that night: the race to the shelter, the awful deflagration, the screams of the wounded and of the dying, the exits buried, the holes one digs with bare hands, and then, the escape amongst the ruins and the corpses, and the profound joy of being alive, even though everything is lost. Most, though, are silent, vanquished by the pain and the memory of the terror they just lived through. They lie on the ground, in the dirt, and they beg for water."

Mer

Mer

Terre

Terre

Pierre

Pierre

Souvenir

Souvenir

Mer

Mer

Terre

Terre

Pierre

Pierre

Souvenir

Souvenir